Alongside my music and articles, I also write children’s books – my previous book, A Hole in the Bottom of the Sea, is a sing-along picture book about the marine food chain that gained worldwide popularity and was even chosen as the flagship book for BookTrust’s National Bookstart Week in 2016.

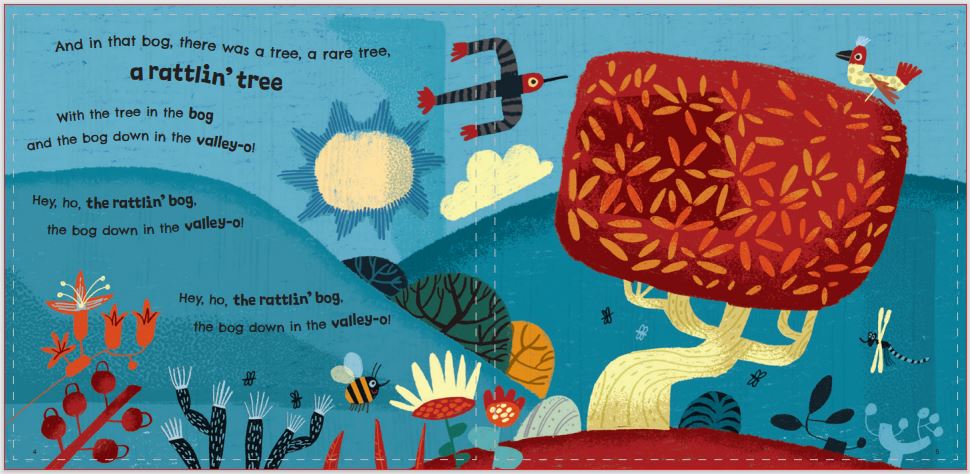

My new book, The Rattlin’ Bog, is out now with Barefoot Books! Based on the catchy Irish folk song of the same name, it introduces young children to life cycles in nature and real-life peat bogs. The text is brought to life by illustrator Brian Fitzgerald, who brings a wonderful character and vitality to the peat bog landscape, and the book includes a link to a rollicking recording of the song by Irish folk band The Speks.

My favourite part was writing the end notes – these are the final pages that include fun facts about the species and themes mentioned in the book. As you can probably imagine, my first draft was literally double the required length, so much of it had to be discarded. However, I thought I would share some of the extra information with you here. That way, if you buy a copy of the book, you can impress your kids with all your additional knowledge!

What is a bog?

Bogs are places where plants grow in really wet ground. If you walked through one, your feet would get very soggy indeed!

Bogs have a kind of soil called peat, which is made when layers of dead plants squash down on top of each other over hundreds of years. Bogs are great at fighting climate change, because the plants that live there absorb carbon dioxide from the air and trap it underground when they die.

But sadly, many of Ireland’s bogs have been destroyed. People dig up the peat to burn in their fireplaces. Or they drain the water out of the bogs so that they can build on them or turn them into farmland.

Thankfully, there are plenty of scientists, leaders and nature lovers like you and me who are working hard to protect Ireland’s bogs and help them to grow back.

Rattlin’ Bog wildlife

Rattlin’ is an Irish word for great or brilliant – and Ireland’s bogs really are a brilliant home for wildlife. Here are just a few of the amazing plants and animals that live there:

Sundew Plant

The Sundew plant has found a way to eat animals! Its leaves are covered in tiny hairs that have drops of sticky liquid on the ends. When an insect lands on a leaf, it gets stuck to the hairs. The leaf curls up, trapping the insect inside. Then the plant digests it just like we digest food in our stomachs!

Irish Hare

During the summer, the Irish Hare’s brown fur helps it to blend in with plants in the bog. But in the winter, its fur changes colour to white so that it can hide in the snow. The hare’s clever camouflage makes it harder for foxes and other predators to catch and eat it.

Sphagnum Moss

Soft, springy Sphagnum Moss grows like a living carpet all over the bog. Because it soaks up rain water like a sponge, it helps the bog to stay damp and to spread out even further. It also contains chemicals that kill germs, so humans have used it to keep food fresh, and even as bandages to cover cuts.

Common Lizard

The Common lizard is Ireland’s only reptile (there are no snakes in Ireland). Unlike most reptiles, it doesn’t lay eggs. Instead, it gives birth to cute little baby lizards. If a predator catches a Common Lizard by the tail, it has a surprising way to escape: its tail snaps off and it grows a new one!

Dragonfly

A bog is the perfect place for a dragonfly to live, because it spends most of its life underwater as a wingless nymph. Then after a few years, it climbs up a plant stalk into the fresh air and sheds its skin. Underneath, it has a pair of folded wings. It unfurls them and flies away!

From egg to bird

Inside the egg, a chick has everything it needs. The hard outer shell protects it. The yolk contains food rich in fat and protein to help it grow. The egg even has a pocket of air for the chick to breathe.

Bird eggs are oval-shaped rather than round, which stops them from rolling out of the nest easily. Many are camouflaged so that predators don’t eat them. The Common Ringed Plover, which nests on beaches, has eggs that look just like pebbles!

When it’s time to hatch, some kinds of chicks chirp to each other from inside the egg so that they all hatch at the same time and get the same amount of care from their parents. Some have an “egg tooth” – a sharp bump on the end of their beak which helps them to smash through the shell. It falls off later.

Being a bird parent is hard work. First, you need to sit on the eggs and incubate them to keep them warm. Then when the eggs hatch, you need to rush back and forth with a constant supply of worms and insects to feed your hungry, growing, noisy chicks. Many bird parents take it in turns, with the mom and dad doing an equal amount of work.

You also have to protect your family and fight off predators. The Northern Lapwing is especially brave – it pretends to have a broken wing to lure predators away from its nest.

But it’s all worth it when your chicks are big enough to fly away and start a families of their own!

From seed to tree

Seeds are similar to eggs in many ways. They have a hard shell on the outside and a food store on the inside. But unlike eggs, seeds can stay asleep for a very long time – until it’s the perfect moment to start growing.

Many seeds sprout when they sense heat and moisture – a sign that spring has arrived. The root breaks out and grows downwards in search of water. The shoot grows upwards towards the sunlight. But if you put a bright light underneath a sprouting seed, the shoot will grow downwards instead!

Once it’s above ground, the shoot unfurls leaves which soak up energy from the sun, while the roots take in water and nutrients from the soil. That’s all it needs to grow into a big, strong tree.

How trees spread their seeds

Trees like to spread their seeds far and wide so that they can find new homes with plenty of space to grow. Here are some incredible ways that they do it:

Mountain Ash

The Mountain Ash grows bright, juicy berries to attract hungry birds. The birds carry the seeds away inside their stomachs and release them in their droppings. The bird poo even acts as fertiliser to help the young trees grow!

Sycamore

Sycamore seeds have little wings attached to them. When they drop off the tree, they spin through the air like a helicopter and get carried far away by the wind.

Tiger’s Claw tree

The Tiger’s Claw tree grows on beaches in tropical countries. Its seeds fall into the ocean and float until they get washed up somewhere new. Sometimes they can travel hundreds of miles!

Giant Redwood

The Giant Redwood only releases its seeds after there has been a forest fire. That way, the young trees will have plenty of room to grow, because the fire has burned big gaps in the forest.

If you’d like to buy the book, it’s available in local bookshops or from any online book vendor. Our preferred online vendors are Waterstones in the UK, Barnes and Noble in the US, and Book City in Canada. Happy reading!

Not only is Nick the guitarist of Jessica Law and The Outlaws, he’s also a talented multi-instrumentalist producer, responsible for arranging and recording my past three EPs. I met Nick when advertising for victims (collaborators! I mean collaborators) in “The Adventures of Sticky Harry and Associates”, a madcap radio play I wrote at university. Since then, we’ve developed an almost psychic level of creative communication, to the extent that he’s actually able to understand and execute phrases such as “electronic doomscape” and “BOM bom BOM bom.” Nick lives in London with his fiancee and numerous pets of varying adorability.

Not only is Nick the guitarist of Jessica Law and The Outlaws, he’s also a talented multi-instrumentalist producer, responsible for arranging and recording my past three EPs. I met Nick when advertising for victims (collaborators! I mean collaborators) in “The Adventures of Sticky Harry and Associates”, a madcap radio play I wrote at university. Since then, we’ve developed an almost psychic level of creative communication, to the extent that he’s actually able to understand and execute phrases such as “electronic doomscape” and “BOM bom BOM bom.” Nick lives in London with his fiancee and numerous pets of varying adorability.